Background

In January 1897, James Philips, the Deputy Commissioner and Deputy Consul General of the Niger Coast Protectorate of what to be later known as Southern Nigeria, travelled to Benin — a city located in the tropical rain forest of Nigeria — alongside eight other Europeans with African retainers. The trip was meant to compel the King (Oba) Ovonramwen of Benin to implement the treaty of free trade made in 1892. The visit coincided with the period when the Oba was performing a ceremony in which he was not supposed to receive visitors. According to the Benin oral sources, Ovonramwen sent a delegation of chiefs to receive the Europeans and persuade them to postpone their visit. However, the messengers decided to disregard their King’s directives, and instead organised an ambush for the visitors at the end of which only two Europeans survived.1

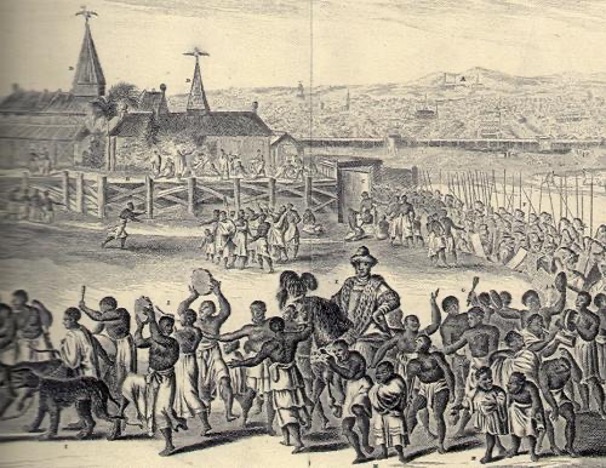

Benin City in the Pre-Colonial Period, 1668, from D. O. Dapper 1686 Description de l’Afrique . . . Traduite du Flamand (Amsterdam: Wolfgang, Waesberge, Boom & van Someren), 320-21.

The British punitive expedition, in February 1897, resulted in the destruction of Benin City and looting of the royal art objects. When the fruit of the Benin pillage reached England, the British Museum tried, unsuccessfully, to be recognised as its owner. The British Admiralty decided to sell the objects at a public auction, and the British Museum had to face competition from German museums. The following table provides the distribution of Benin objects in some selected German and British museums, according to the record taken by the historian Von Luschan in 1919:

The Distribution of Benin Art Works in Britain and Germany2

| Museum | Number of Objects |

| Völkerkunde Museum, Berlin | 580 |

| Hamburg Museum | 196 |

| Dresden Museum | 182 |

| Museum of Cologne | 76 |

| Museum of Frankfurt | 51 |

| British Museum | 289 |

| Pitt Rivers Museum | 271 |

The acquisition of the Benin objects and more broadly African cultural artefacts in European museums has resulted in the production of literature on the history of such objects in Western scholarship. Such an enterprise often neglects the complexities surrounding these cultural objects. In the early decades of the twentieth century, most of the writings on Benin Art re-echoed the rhetoric of colonial justification — the Africans being uncivilised and in dire need of European guidance. It was from this perspective that a narrative was contrived to link the Benin art with Asian migrants, and in other accounts the Portuguese or even the Islanders of Atlantis.3

However, since the late colonial period, critical discourses exploring a new paradigm in making sense of colonial subjugation have foregrounded the voices of the colonised. Even this new regime of truth is often parochial as it begins and ends in crafting a perspective that emphasises cultural achievements of the continent. While this approach departs significantly from the colonial rhetoric, there is still a tendency to be locked up in a mere glorification of Africa as a provenance of a great civilisation while ignoring, or even more appropriately silencing, the competing perspectives surrounding the objects which represent the civilisation.

Competing Narratives: The Benin Plaque

A Plaque Depicting Oba and Europeans held in the British Museum. Museum number Af1898,0115.23 (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0).4

Neil MacGregor’s BBC Radio 4 programme (and subsequent book), A History of the World in 100 Objects of 2010 attempted to reconstruct the biography of the Benin Plaque.5 However, as typical of such reconstructions, it ended up extolling the Plaque and its makers while ignoring the place of object-making in Benin culture. Thus, it privileges academic interpretation over the Benin peoples’ voices. While departing in significant ways from MacGregor’s intervention, this biography is premised on conceptually exposing the enormous complexity of and the multitude of questions relating to the Benin Plaque, specifically, and African Artworks, more broadly.

In reconstructing the biography of the Benin plaque, at least three competing narratives have to be accounted for: the local narrative, the national version of the narrative and the international projection of the object.6 The plaque depicting the Oba, his two chiefs and two Europeans is about 40 centimetres (16 inches) square. The two titleholders were the Osa and Osuan. The King is distinguished by the composition of the hat he was wearing, which was made of beads while the headgear of his subordinates were of raffia palm.7 The event they were celebrating was Igue ceremony which was initiated by Oba Ewuare (1440–1473) who is remembered as the greatest ruler of Benin who transformed it from a small political entity into an empire. He rebuilt the empire and introduced reforms that severely checked the powers of the chiefs. Perhaps to project his eminence and command obedience, he instituted this ceremony which is meant to strengthen — and I suppose to display — Oba’s mystical powers. The main highlight of the event is the sacrifice of predators and rubbing of Oba’s body with magical charms. Animals hold a vital position is Benin Art. At times they epitomise kingship. The sacrifice is meant to prove that the Oba holds enormous power.

In all probability, the plaque represents Oba’s superiority over the Europeans. Among all the Benin ceremonies, Igue is unique in its personification of Oba’s pre-eminence. This can be gleaned from the projection of the two Europeans in small images while the Oba and his subordinates have been foregrounded. This perhaps exemplifies the superiority of the Oba over his visitors. The craft of plaque making, according to the Benin place historians, is traced back to the sixteenth century.8 The technology of brass work, on the other hand, is dated back to the period of Oba Oguola, the sixth king of the Oba dynasty. This may have been the first quarter of the fourteenth century.9 Archaeological findings, however, have suggested the artistic use of copper from at least thirteenth century.10 A popular tradition recounted how the Oba requested from the neighbouring powerful kingdom of Ife to provide an expert who would transmit the technique of brass casting to the Benin people. This was meant to stop the old practice of receiving “a headpiece of shining brass”11 from Ife as an endorsement of the new Oba’s authority. This tradition has been reported by the Portuguese who visited the empire in the sixteenth century.12

The plaques and other artworks, according to Benin tradition, are historical records, mnemonic devices or spiritual objects.13 As historical documents, they help us contextualise Benin history in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. In a complex society like Benin, the meanings of the art are encapsulated in people’s proverbs, tales and language. Once stripped from their context, the objects lose the very purpose for their creation. The modern curatorial tradition dominant in Europe — where the objects are appreciated primarily as the work of art — is alien to the cultural functions the artefacts are meant to serve.

The image of the objects is imbedded in Benin culture and language. In Edo language, “the expression to commemorate (sa-e-y-a-ama) literally means to cast a pattern in brass.”14 The notion of commemoration is linked to the image of liquid which gets hardened as the way memory is solidified into the preservation of history. Working with brass is a highly ritualised process. The artists have to sacrifice animals for their protection. Brass is associated with Ogun, the deity identified with agriculture, hunting, war and transport.

The national projection of the Benin artworks entails contriving a narrative which emphasises connectedness among different regions of Nigeria. The Benin objects are linked to Nok and Igbo Ukwu art culture. The Nigerian artworks are displayed in local and international exhibitions by the state-owned museums as the repository of unity in diversity. This is often in conflict with the local agitation for the restitution of the artefacts. That is why one of the central issues raised by some critics is the question of the legitimate owner of the loot taken from Nigeria in 1897. Are they to be restituted to the Benin Kingdom — in case it has been decided that they will be returned to their places of provenance — or the Nigerian government?15 This question exposes the enormous tension these powerful cultural objects represent. Another issue that follows as a result of the above is how do you justify getting back the artworks from the various European museums since they were acquired legally from the British?

Another central question connected to the plaques and the Benin and Ife art more broadly is the tendency to give undue attention to the study of the Benin Art at the expense of the other centres of civilisation. This also entails portrayal of Benin Art not only as autochthonous but as also responsible for the creation of political entities in the region in the fifteenth century. The discovery of Igbo Ukwu bronze casting culture associated with the ninth century has proven the more ancient origin of the culture vis-à-vis Benin Art. It was found that the bronzes of Igbo Ukwu were independent of both Ife and Benin and style. This radically challenged the thesis which held Ife and Benin as the fountainhead of culture and civilisation in Southern Nigeria.16

Conclusion

The plaque and other artworks of Benin that are in custody of Museums in Nigeria and other parts of the world are powerful cultural objects that represent competing narratives and they can help us understand the pre-colonial history of the Kingdom. This is especially significant because of the shortage of written records on that aspect of its history. Even the accounts provided by the Portuguese dating back to the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries posed serious challenges for historical interpretation. They hardly provided comprehensive information on the rulers that could be used to provide an accurate chronology of political history of the Kingdom. Realizing the need to preserve their history for posterity, the people of Benin wrote their stories in bronze and brass sculpture. Instead of turning to our present standard of interpretation or imprisoning the objects in museums — to be appreciated as works of art — as enshrined in the dominant curatorial ritual, the makers of these artefacts would expect the future generations to dig deeply to unravel that story the objects represent.

1 See Bryna Freyer, Royal Benin Art in the Collection of the National Museum of African Art, (Washington, DC: National Museum of African Art, Smithsonian Institution Press, 1987), 10; Jacob Egharevba, A Short History of Benin, (Ibadan: Ibadan University Press, 1968), 49.

2 See Louis Carré, “Benin — The City of Bronzes” Parnassus, Vol. 8, No. 1 (1936), 13 – 14. The list is, by no means a representation of the entire objects in European museums. According to the list provided by Philiph John Crosskey Dark, Benin artworks can be found in more than fifteen museums in Germany alone. They can also be found in other European countries such as Australia, Austria, Belgium, Denmark, etc. See Philiph John Crosskey Dark, An Introduction to Benin Art and Technology, (Oxford: Clarendon Press), 78 – 81.

3 See Carré, “Benin — The City of Bronzes,” 15.

4 Available online, http://art-in-space.blogspot.com/2015/10/anonymous-benin-bronze-oba-with.html.

5 See Neil MacGregor, A History of the World in 100 Objects, (London: Allen Lane, Penguin Books, 2010), Object Number 77.

6 For the implication of the three narratives in the case of the Nigerian NOK culture, see Samaila Suleiman, “The Nigerian History Machine and Production of Middle Belt Historiography,” (PhD Dissertation, University of Cape Town, 2015), 153.

7 See Paula Ben-Amos, The Art of Benin, (New York: Thames and Hudson, 1980), 89.

8 The date used here is based on reconstruction from the account of a Benin place historian and others recorded in 1897, see Freyer, “Royal Benin Art,” 43.

9 Dark, An Introduction to Benin Art, 46.

10 See Graham Connah, “Archaeology in Benin,” The Journal of African History, Vol. 13, No. 1 (1972), 38.

11 See Thomas Hodgkin, Nigerian Perspectives, an Historical Anthology, (London: Oxford University Press, 1960), 124.

12 Since the fifteenth Century when the first set of Portuguese visited Benin Kingdom until the nineteenth century, the relationship between the two sides was primarily based on trade and Christian Evangelism. The Kingdom obtained European goods in exchange for slaves. The imperialist motive arose from the desire to primarily protect the economic interest of the European firms in the nineteenth century leading to the invasion of the Kingdom in 1897 as noted above.

13 Barbara Plankensteiner, “Benin: Kings and Rituals: Court Arts from Nigeria,” African Arts, Vol. 40, No. 4 (2007), 76.

14 See Paula Girshick Ben-Amos “Brass Never Rusts, Lead Never Rots’: Brass and Brass Casting in the Edo Kingdom of Benin.” in Frank Herreman, (ed.) Material Differences: Art and Identity in Africa, (New York: Museum of African Art, 2003), 110 – 111.

15 For the multiple of questions these object raise, see Elazar Barkan, “Aesthetics and Evolution: Benin Art in Europe” African Arts, Vol. 30, No. 3, Special Issue: The Benin Centenary, Part 1 (1997), 41.

16 See A. E. Afigbo, “The Anthropology and Historiography of Central-South Nigeria before and since Igbo-Ukwu” History in Africa, Vol. 23 (1996), 1–15; Chike C. Aniakor, “Do All Cultural Roads Lead to Benin?” The Missing Factor in Benin and Related Art Studies: A Conceptual View,” Paideuma: Mitteilungen zur Kulturkunde, 43 (1997), 301 – 311.

what an awesome piece. Kudos to the historian that documented this.

LikeLike

A Round Claff for the Wonderful And Great Job.

More Blessings !

LikeLike

What a beautiful and wonderful history! The history is full of drama and intrigue

LikeLike